Fresh Insights in Sustainable Food & AgTech

Discover the ideas, people, and practices growing a healthier food future.

Why low-friction reformulation is now a strategic imperative for food producers

The most advanced taste tool we have is still a Chef

Yuka: The Reformulation Pressure Food Producers Didn’t Vote For

The Fibre Factor: Why the Fibre Gap Is a System Design Problem

Upcycling as Infrastructure: Why UPP Joined the Upcycled Food Association

Feeding the next phase of food: What GLP-1s reveal about nutrition, not medication

The Cocopopification of Food (and Why Fighting the Industry Won’t Fix It)

Fork From Farm: Designing Food Around What People Need

If people won’t change their diet to save their lives, why would they change it to save the planet?

Clean ingredients that sound natural - and why that suddenly matters again

A World Without Cows: What happens when we optimise the wrong variable?

Smart hybridisation: How to scale impact before you scale volume

Balanced Proteins: Quiet Scale Beats Loud Disruption

Ingredient stacking: the fastest route to lower-carbon food that still tastes like food

Make Sustainability a By-Product of Efficiency: How Smarter Food Systems Outpace Traditional “Green” Narratives

Europe after peak: why the next era of food is about nutrition density, not volume

The system isn’t broken. It’s optimised.

7 Rules for Integrating Sustainable Protein Ingredients at Industrial Scale

The Cocopopification of Food (and Why Fighting the Industry Won’t Fix It)

There’s a feeling many consumers share, even if they don’t have the words for it. Food has become… cartoonish. Too sweet. Too smooth. Too engineered. Too loud. Too moreish. Too far from anything you’d recognise in a kitchen.

It’s the "cocopopification" of food: products designed to be hyper-palatable, hyper-convenient, and hyper-repeatable — optimised less for nourishment and more for throughput.

And it’s triggered a backlash.

The book Ultra-Processed People didn’t create the concern — it simply gave it a clear narrative:: "something about the modern diet feels wrong." And people aren’t imagining it.

Should we only eat unprocessed food? No.

That idea sounds clean, but it collapses the moment it meets reality.

Because “only unprocessed” assumes a world where everyone has:

time to cook from scratch every day

stable income and access to fresh ingredients

predictable schedules

equipment, skills, and energy

low stress and high capacity

That is not most people’s life.

It’s not how modern societies work.

Processed food exists for a reason: it made food safer, cheaper, more available, more stable, and more consistent. It reduced hunger. It extended shelf life. It supported working households. It enabled scale.

The mistake isn’t that food is processed.

The mistake is that processing became a proxy for quality.

And then the system got too good at optimising for the wrong thing.

Should we have better food?

Definitely. But “better” doesn’t mean nostalgic.

It means upgraded.

Better food is food that fits modern life and delivers what bodies actually need:

more nutrition density

more fibre

better satiety

fewer empty calories

fewer unnecessary functional crutches

ingredients that behave like food, not chemistry

Better food is not a return to the past.

It’s a redesign of the default.

Can we get there without working with the industry?

Impossible.

Because the industry is the system.

And the system is how food reaches people.

It’s easy to imagine that the solution is to “beat Big Food” — to replace it, shame it, regulate it into submission, or boycott it into collapse.

But that approach misunderstands something important:

food at scale doesn’t change through moral pressure alone.

It changes through supply chains, specifications, manufacturing realities, retailer requirements, cost constraints, and consumer repeat purchase.

It changes when the people inside the system have better tools.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: The people inside the industry eat the same food we do.

They are not a separate species. They are parents buying dinner. They are commuters grabbing lunch. They are shoppers managing budgets. They are humans with the same constraints and cravings.

The idea that the industry is a villain, and consumers are the victims, makes for a satisfying story. But it doesn’t build a better food environment.

The story of modern food is also the story of progress

Look at the UK over the last century.

From 1900 through to around 2011, life expectancy rose markedly — with temporary shocks during wars and pandemics. Multiple forces drove that improvement: public health measures, medical advances, and better living conditions.

But food played a role too.

Improved food security.

More reliable calories.

More consistent nutrition.

Less seasonal hunger.

Safer supply.

The system delivered.

And that matters, because it’s easy to criticise the modern food environment without acknowledging what it replaced.

But now the optimisation target has shifted.

The problem today isn’t scarcity.

It’s abundance — in the wrong direction.

And more recently, rising obesity and chronic disease risk linked to diet and inactivity threaten to slow progress, especially in healthy life expectancy.

So if we want continued gains, something has to change.

Not in theory.

In the everyday food environment people actually live in.

The modern food environment is shaping outcomes by default

Most people don’t fail at nutrition because they lack willpower.

They fail because the environment is doing what it was designed to do:

cheap calories are everywhere

ultra-convenient formats dominate

products are engineered for repeat purchase

the easiest option is rarely the best one

“healthier” often costs more or tastes worse

So the system produces predictable outcomes.

And then we blame individuals for responding normally.

That’s not a health strategy.

That’s a design failure.

The solution isn’t to reject the system. It’s to transform it.

If you want a healthier population, you need healthier defaults.

Not niche alternatives for the already motivated.

That means changing what happens inside the categories people already buy:

ready meals

sauces

bakery

snacks

kids’ food

everyday staples

It mens improving the inputs, not just preaching about the outputs. And it means working with manufacturers — because manufacturers control the levers of scale:

formulation

cost-in-use

texture and taste

shelf life

labelling

procurement

production realities

This is not glamorous work. But it’s the only work that scales.

A new goal: keep the convenience, upgrade the nutrition

The future isn’t “everyone eats whole foods all the time.”

The future is that the convenient foods people already rely on become:

more nutritious

less empty

less dependent on ultra-processing tricks

more aligned with long-term health

Not through disruption.

Through upgrade paths.

Small improvements repeated across high-volume products become population-level change.

That’s the game.

What we’re doing at UPP

At UPP, we’re not trying to tear the system down.

We’re trying to make it better at what it already does: feed people at scale.

That means working upstream - turning under-utilised vegetables into functional ingredients that can be used in real manufacturing to improve food from the inside out.

Not as a “health product.”

Not as a premium niche.

As an ingredient-level upgrade that fits the realities of modern food:

affordability

safety

scale

consistency

compatibility

Because beating the industry isn’t the answer.

Helping the system transform is the answer.

And that is what we are doing.

Closing thought

The cocopopification of food didn’t happen by accident.

It happened because the system was optimised for what it was rewarded for.

Now the rewards are changing.

And if we want the next century of progress - not just in life expectancy, but in healthy life expectancy - we need the modern food environment to change too.

Not by wishing processing away.

But by making processed food worthy of the role it plays.

Clean ingredients that sound natural - and why that suddenly matters again

For years, the food industry has treated “clean label” as a marketing problem.

Remove an E-number.

Use "store cupboard ingredients"

Reduce the length of ingredient declarations on back of pack.

What’s changed recently is not the existence of processed food - it’s the level of public scrutiny around how food is processed, why, and whether the trade-offs are still justified. The debate has re-entered the mainstream.

From Joe Wicks: Food for Fitness to the success of Chris van Tulleken’s “Ultra-Processed People”, consumers are being exposed - often for the first time - to the idea that not all processing is equal, and that formulation decisions made far upstream can shape health, trust, and perception downstream.

For food producers, this creates a familiar tension.

The system still needs processed food.

Scale still requires consistency, safety, and shelf life.

Cost pressure has not gone away.

But the tolerance for ingredients that sound synthetic, opaque, or unnecessary is narrowing. And that matters — not because of ideology, but because perception now influences risk.

The quiet return of ingredient scrutiny

What’s striking about the current moment is how little it resembles previous “clean eating” cycles. This is not about superfoods or exclusion diets.

It is about processing logic.

Both the documentary and the book focus less on individual nutrients, and more on the architecture of modern food: fractionation, recombination, texture engineering, and the substitution of whole-food function with isolated additives.

That framing resonates because it aligns with something food manufacturers already know internally: Many formulation decisions were made to solve industrial constraints - not nutritional ones.

Those decisions made sense at the time. But some of their side-effects are now visible to consumers in a way they weren’t before.

Why “natural-sounding” ingredients are not about optics

There’s a temptation to treat this moment as a communications challenge.

Change the language.

Control the narrative.

Re-educate the consumer.

That approach misses the point.

What consumers are responding to is not branding — it’s credibility. Ingredients that sound natural tend to share three characteristics:

They originate from recognisable crops or processes

They perform multiple functions, rather than replacing each one with a separate additive

They can be explained without a chemistry lesson

This is not nostalgia. It’s cognitive load. When ingredient lists become shorter and more intuitive, trust increases - even if the product remains processed.

Processing is not the enemy - fragmentation is

One of the most unhelpful conclusions drawn from the “ultra-processed” debate is that processing itself is the problem. It isn’t.

Processing is what allows food to be safe, affordable, and widely available.

The issue is how fragmented processing has become.

Over time, many foods have been deconstructed into ever more specialised inputs -stabilisers, emulsifiers, texturisers, isolates - each solving a narrow technical problem, often sourced from different global supply chains. The result is food that works industrially, but looks and feels increasingly abstract to the people eating it.

Reversing that trend does not require abandoning processing. It requires re-integrating function.

When one ingredient can do the work of many

From a formulation perspective, the most powerful ingredients today are not the most novel. They are the ones that:

deliver protein, fibre, and functionality together

replace multiple additives with a single crop-derived input

integrate into existing processes without re-engineering lines

arrive with procurement-grade traceability and allergen clarity

This is where “clean” stops being about purity and starts being about efficiency - fewer ingredients, fewer suppliers, fewer explanations.

For manufacturers under pressure to reduce cost, risk, and Scope 3 emissions simultaneously, this matters more than philosophy.

Clean labels as a by-product of better system design

The most scalable changes in food rarely happen because consumers demand them explicitly. They happen because producers redesign systems in ways that quietly remove friction.

When ingredients are:

derived from familiar crops

processed through transparent, auditable systems

supplied regionally rather than globally

used to replace several additives at once

the label improves as a side-effect.

Not because anyone set out to chase a claim — but because the system became simpler.

That distinction is important.

Why this matters now - commercially, not culturally

The current focus on ultra-processing will not last forever. But its effects on risk perception, retailer scrutiny, and regulatory attention already matter. For food producers, the question is not whether to respond – it is how.

High-friction reformulation in response to public pressure often creates more problems than it solves.

Low-friction reformulation - using ingredients that behave like food, sound like food, and come from food - creates optionality.

It allows producers to:

simplify labels without compromising performance

reduce additive dependency without redesigning factories

respond to current media pressure without chasing trends

future-proof portfolios against shifting definitions of “acceptable” processing

That is not a consumer strategy. It is a resilience strategy.

Closing thought: familiarity scales faster than novelty

The food system does not need to swing from hyper-processed to idealised whole foods. It needs better integration between agriculture, processing, and formulation - so that ingredients once again look and feel like they belong in food.

In a world where scrutiny is rising but tolerance for disruption is low, the safest path forward is not to fight processing - but to make it quieter, simpler, and easier to explain.

Clean ingredients that sound natural are not about going backwards. They are about rebuilding trust - one formulation decision at a time.

Read more here.

Fork From Farm: Designing Food Around What People Need

Grow it. Process it. Package it. Sell it. Eat it.

It’s a neat story. It sounds logical. It sounds efficient.

But it hides a fundamental flaw:

It starts in the wrong place.

Because the farm doesn’t exist to express its own potential. It exists to feed people. And people don’t buy crops.

They buy outcomes.

They buy dinner.

They buy convenience.

They buy familiarity.

They buy nutrition (even when they don’t call it that).

They buy something that fits their life, their budget, and their taste expectations.

So if we want to build a better food system, we need to invert the logic.

Not farm to fork...Fork from farm.

Start with what people need — then work backwards.

The fork is the specification

In most industries, product design begins with the user.

Food is one of the few sectors where we often pretend the opposite is true.

We treat supply as destiny:

“This is what we grow.”

“This is what we harvest.”

“This is what we can process.”

“So this is what people will eat.”

But consumers don’t eat what exists....They eat what works.

And “works” is a demanding brief:

it has to taste good

it has to feel right

it has to be affordable

it has to fit into habits

it has to be safe

it has to be available consistently

it has to deliver real nutrition in familiar formats

That’s the fork...That’s the spec.

And when you start there, you stop building food systems around what’s easiest to produce — and start building them around what’s actually needed.

The real problem isn’t waste. It’s under-utilisation.

Waste is usually framed as a moral failure.

Something is thrown away. Something is “lost.” Something is “not valued.”

But that framing misses the point.

In modern food systems, waste is often just a symptom of something more structural: We’ve built supply chains that can’t fully use what already exists.

Not because the material isn’t good. But because it doesn’t fit the system:

wrong format

wrong size

wrong spec

wrong shelf-life

wrong processing behaviour

wrong economics

wrong route to market

The issue isn’t that food is wasted....It’s that it’s not engineered into value. And that’s a solvable problem.

At UPP, we focus on a different question: How do we fully utilise what we already grow — and turn more of it into food people actually want to eat?

Not as a side project.

As the core design principle.

Fork from farm changes the optimisation target

Most food systems have been optimised around three things: cost, safety, and scale.

That optimisation delivered real progress.

It made food affordable. It made food safe. It made food reliable.

But now the brief has expanded.

The system is being asked to deliver more:

higher nutrition density

more resilience

more supply security

more efficiency

more stable economics for farmers

and fewer trade-offs

The old approach tries to solve this by adding more complexity.

New ingredients. New supply chains. New consumer behaviours. New formats.

But complexity doesn’t scale cleanly in food.

The better approach is to upgrade the system we already have.

And that starts by rethinking directionality.

What happens when you build backwards from the consumer?

When you design from the fork backwards, three things become possible at once.

1) National food security improves: Food security isn’t just about growing more. It’s about converting more of what we already grow into stable, saleable, nutritious food. If a country can take a higher percentage of its domestic crops and turn them into:

consistent ingredients

predictable inputs for manufacturing

scalable products people actually buy

…then the system becomes less exposed to shocks.

Less dependency.

Less volatility.

More resilience.

Food security is often treated as a geopolitical issue. But a lot of it is simply an engineering issue: How efficiently can you convert what exists into food that fits demand?

2) Consumers get more nutritious food - without needing to change:. There’s a persistent myth in food innovation that better nutrition requires better behaviour. That if we want healthier outcomes, consumers need to:

cook more

read labels

change habits

“make better choices”

Sometimes they will. But at population scale, behaviour change is a weak lever.

The high-impact route is the opposite: Keep the products. Upgrade the inputs.

That means nutrition delivered through the formats people already buy and trust.

More fibre.

More micronutrients.

More functionality from real ingredients.

Not as a new category. As an upgrade path.

That’s how change compounds.

3) Farmers become more financially sustainable. Farm economics don’t collapse because farmers aren’t productive. They collapse because value capture is thin - and too much of what’s grown is trapped in low-value channels. When utilisation is low, margin disappears into:

grading and rejection

price compression

commodity exposure

limited end markets

low flexibility in what can be sold

But when you can convert more of what is grown into ingredients that manufacturers can actually use - at scale - something shifts.

The farmer stops being a price-taker for a narrow output.

And starts being part of a system that creates value from a broader slice of the crop.

That’s not charity.

That’s better system design.

This is what UPP is building: utilisation as a strategy

At UPP, we don’t see ourselves as a “waste solution.”

Waste is the headline.

Utilisation is the mechanism.

We take vegetables that are under-utilised — not because they’re undesirable, but because they’re hard to integrate — and we turn them into ingredients that work inside real manufacturing.

That means designing for:

spec consistency

supply reliability

manufacturability

nutritional value

compatibility with existing formats

and commercial reality

Not reinvention. Upgrade.

Because the system doesn’t need a lecture. It needs tools.

A better question than “what are we wasting?”

The traditional sustainability conversation starts with guilt: “How much are we wasting?”

The better conversation starts with design: "How much of what we already grow can we turn into food that people actually need?"

That shift matters.

Because it doesn’t just reduce waste. It increases:

food security

nutrition access

farm resilience

manufacturing efficiency

and the ability to scale change without breaking the system

That’s fork from farm.

Not a slogan.

A direction of travel that actually works. And that is what we at UPP are delivering.

Feeding the next phase of food: What GLP-1s reveal about nutrition, not medication

GLP-1 medications are changing how people eat - whether the food system is ready or not. Drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy are often discussed through the lens of weight loss or healthcare costs. But from a food systems perspective, they reveal something more fundamental: how poorly aligned much of today’s food supply is with the way people actually need to eat.

Reduced appetite.

Smaller portions.

Higher sensitivity to texture and satiety.

When people eat less, what they eat matters more.

This isn’t a niche issue. As GLP-1 use expands - and as many consumers eventually taper or come off medication - the demand for foods that are nutrient-dense, gentle on digestion, and affordable will only grow.

The opportunity is not to medicalise food.

It is to make food do its job better.

Smaller meals expose a big problem

For decades, food formulation has optimised for:

volume

palatability

cost per calorie

That model works when consumption is high. It breaks down when it isn’t.

When people eat smaller portions - whether due to GLP-1s, ageing populations, or shifting health priorities - foods that are:

low in fibre

low in protein

highly fractionated

nutritionally diluted

stop making sense.

The next phase of consumer food is not about eating less food. It is about eating more nutrition per bite.

Broccoli is a nutritional outlier - not a trend ingredient

Broccoli is not fashionable.

It is not novel.

It does not need a story.

It is, however, unusually dense in:

fibre

protein (relative to vegetables)

micronutrients

bioactive compounds

And yet, a significant proportion of the broccoli grown in Europe and the UK never enters the food system at all.

Leaves, stems, and surplus florets are routinely left in fields or diverted to low-value pathways - not because they lack nutrition, but because the system is not designed to use them. That is where opportunity lives.

Nutrition density without asking consumers to “try harder”

One of the persistent mistakes in food innovation is assuming that better nutrition requires:

behaviour change

premium pricing

unfamiliar ingredients

In reality, most consumers — including those on or coming off GLP-1 medication — want food that is:

familiar

affordable

easy to tolerate

quietly more nutritious

Broccoli-derived ingredients offer exactly that.

When converted into functional protein and fibre ingredients, they can:

increase satiety in smaller portions

support digestive tolerance

deliver nutrition without heaviness

integrate into existing food formats

No new habits required.

Coming off GLP-1s: where food matters most

Much of the public conversation focuses on starting GLP-1s. Less attention is paid to what happens after.

As people reduce or discontinue medication, food becomes the primary stabilising force:

maintaining satiety

supporting metabolic health

preventing rebound through nutrition, not restriction

This is where nutrient density beats calorie control. Foods that deliver protein and fibre together - in familiar, everyday formats - help bridge the gap between medical intervention and long-term eating patterns.

Not as “diet food”.

As better food.

Why affordability determines whether this scales

Nutrition that only works at a premium price point doesn’t scale.

At UPP, our focus is not on extracting novelty from broccoli - it is on extracting value from what is already grown and wasted.

By using under-utilised broccoli biomass:

farmers gain a new income stream

ingredients are lower cost than many imported alternatives

manufacturers improve margins rather than sacrificing them

consumers access better nutrition without paying more

That matters — because GLP-1 use is not limited to affluent consumers, and neither is the need for nutritious food.

System change, not product theatre

The most important shift here is upstream.

Instead of designing products around consumer willpower, the system can:

reformulate existing foods to be more nutrient-dense

improve satiety without increasing portion size

reduce reliance on globally sourced isolates

quietly align food with emerging consumption patterns

This is low-friction change — the kind that actually reaches scale.

Broccoli as infrastructure, not a hero ingredient

UPP does not position broccoli as a superfood or a solution in isolation. We treat it as infrastructure:

a crop already grown at scale

with nutrition already proven

currently under-utilised due to system inefficiency

By turning wasted broccoli into functional food ingredients, we connect:

agriculture

processing

formulation

and health outcomes

Without asking consumers to think about any of it.

A food system ready for what’s next

GLP-1s didn’t create the need for better food. They exposed it.

As people eat less - by choice, by health, or by circumstance — the food system has to respond with:

higher nutritional yield

better use of what we already grow

and economics that work for everyone involved

Broccoli isn’t the future because it’s new.

It’s the future because it’s already here — and we haven’t been using it properly.

Better for farmers.

Better for producers.

Better for people.

Better for the planet.

That’s not a dietary philosophy.

It’s a systems outcome.

Read more here.

The Fibre Factor: Why “eat more fibre” won’t scale unless we change how food is made

Fibre is having a moment.

Not in the way protein did - with a thousand new SKUs and a marketing arms race — but in a quieter, more structural way. It’s re-entering the mainstream conversation as something we’ve lost, something we need, and something modern diets are failing to deliver.

The BBC series The Fibre Factor (BBC Radio 4 - The Fibre Factor), presented by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, captures that shift well. Across five episodes - from Munching Plants to Manufacturing through to fibre fortification, beans, and “fibremaxxing” - it asks a simple question with uncomfortable implications:

If fibre is so foundational to health, why are we eating so little of it?

The answer isn’t ignorance. It’s system design.

We didn’t “forget” fibre. We engineered it out.

The first episode’s historical arc is useful because it reframes fibre not as a new discovery, but as a baseline that modern food quietly moved away from.

For most of human history, diets were structurally fibre-rich because they were built around whole plants: roots, leaves, seeds, legumes. Fibre wasn’t a target. It was a default.

Then industrialisation did what industrialisation always does: it optimised for throughput, shelf life, uniformity and cost. And in the process, fibre became collateral damage.

Refining grains removes bran. Fractionating plants separates function. Ultra-processing turns whole food architecture into inputs and additives.

Nobody set out to create a low-fibre world. It’s simply what happens when you optimise food for industrial efficiency without simultaneously optimising for nutritional outcomes.

“Fibremaxxing” is a signal — but behaviour change is still a weak lever

Episode 2 introduces “fibremaxxing”, the online trend pushing people to deliberately chase fibre targets the way they once chased protein.

That’s interesting - not because trends solve systemic problems, but because they reveal a rising demand for tools people can act on. The public is looking for a new anchor: not restriction, not purity, but something measurable that maps to health.

But even if fibremaxxing is here to stay, it won’t close the gap at population scale.

Most people won’t track fibre long-term. They won’t weigh beans, count grams, or redesign their meals every day. Not because they’re lazy, but because food decisions sit inside real constraints: time, budget, habit, family preferences, and what’s available. This is why behaviour change remains unreliable as a primary strategy.

If we want fibre intake to rise meaningfully, it has to happen upstream — through how everyday food is formulated.

The real question isn’t “can we eat more fibre?” It’s “can we build fibre back into defaults?”

Episode 3 goes directly to the core issue: the foods that dominate modern diets — bread, pasta, rice, packaged meals — are often fibre-poor by design. So the problem isn’t solved by telling people to eat like nutritionists.

It’s solved by improving the foods people already buy.

This is where the industry’s next phase becomes clear:

Can we fortify staples without compromising taste and texture?

Can ultra-processed foods ever become fibre-rich?

Can we do it without raising cost, breaking supply chains, or adding ingredient-list complexity?

These aren’t consumer questions. They’re manufacturing questions.

And they point to the same conclusion we keep coming back to: low-friction reformulation is the only approach that scales.

Because reformulation doesn’t fail due to lack of ambition. It fails due to friction: process disruption, sensory risk, procurement uncertainty, and complexity that slows decision-making.

Beans are the obvious answer — and the hardest one to mainstream

Episode 4 focuses on beans and pulses, and it’s hard to argue with the case: beans are fibre-rich, affordable, nutritionally dense, and comparatively low-impact.

They are also, in the UK at least, under-consumed outside a narrow set of formats (the baked bean exception is telling).

This is a classic example of a food that makes perfect sense on paper but struggles in practice. Not because beans are “bad”, but because the system around them isn’t built to make them effortless.

You can’t scale fibre by asking the whole population to suddenly love lentils.

You scale fibre by embedding it into familiar formats — the foods people already eat — without requiring a cultural conversion.

The future of fibre is not a new diet. It’s better formulation.

By the final episode, the series moves toward solutions: activism, education, cooking, and community-level change.

All of that matters. But the biggest lever still sits upstream.

If the UK is serious about addressing obesity and diet-related disease, fibre has to stop being a personal responsibility and start becoming a system outcome.

That means ingredients and processes that make it easier for manufacturers to:

increase fibre content without wrecking sensory performance

simplify formulations rather than “add another additive”

keep products affordable

work inside existing lines and supply chains

This is exactly why fibre is not just a nutrition story. It’s an ingredient infrastructure story.

At UPP, we think about fibre the same way we think about protein and sustainability: not as a claim, but as a design constraint. The question is never “how do we convince people to eat differently?”

It’s “how do we improve everyday food without asking people to try harder?”

Because when you change what goes into food — quietly, at scale — you change what comes out of the system.

And that’s how fibre stops being a trend, and becomes a default again.

Why low-friction reformulation is now a strategic imperative for food producers

For much of the past decade, reformulation has been framed as a question of innovation.

New ingredients.

New processes.

New claims.

In practice, however, reformulation rarely fails because food producers lack ambition. It fails because it introduces too much friction into systems that are already under pressure.

Today’s manufacturers are balancing cost volatility, labour constraints, Scope 3 emissions targets, retailer scrutiny, and increasingly conservative capital environments - all while maintaining taste, texture, safety, and margin. In that context, the most valuable ingredient innovations are not those that promise transformation, but those that enable change without disruption.

Low-friction reformulation is no longer a “nice to have”. It is becoming a strategic requirement.

The hidden cost of reformulation friction

Every reformulation introduces risk - but not all risks are equal.

High-friction reformulation typically brings some combination of:

changes to existing processing lines

new allergen or regulatory complexity

uncertain supply at scale

unproven sensory performance

additional approval cycles with retailers

Each one compounds internal cost and slows decision-making. Even when the sustainability case is strong, these frictions often stall progress long before products reach shelf.

This is why many reformulation programmes quietly revert to incremental tweaks, rather than the step-changes that sustainability, resilience, and cost pressures increasingly demand.

Why the industry’s constraints have changed

What’s different now is not consumer intent — it’s operating reality.

Food producers are operating in an environment where:

ingredient volatility is structural, not cyclical

labour availability is constraining agricultural and processing inputs

Scope 3 accountability is shifting from aspiration to audit

capital discipline matters more than speed

In this environment, reformulation strategies that rely on novel biology, bespoke infrastructure, or fragile supply chains are harder to justify - even if they are technically impressive. The winning strategies are those that reduce risk while delivering change.

Low-friction reformulation: what it actually means

Low-friction reformulation is not about avoiding innovation. It is about designing innovation around existing food systems, rather than asking food systems to adapt around innovation.

In practical terms, it means ingredients that:

integrate into existing manufacturing processes with minimal modification

behave predictably across standard unit operations (hydration, cooking, freezing, extrusion, etc.)

arrive with procurement-grade documentation: traceability, allergen clarity, country of origin, and certification

are available at meaningful scale from reliable, regionally anchored supply

reduce environmental impact without introducing consumer unfamiliarity

This is not a compromise position. It is a deliberate strategy to unlock adoption at speed.

Why system-level thinking matters more than ingredient novelty

One of the consistent lessons across food innovation is that isolated optimisation creates downstream problems.

A low-carbon ingredient that requires a fragile supply chain creates operational risk.

A cost-effective input that introduces new allergens increases approval friction.

A novel protein that excites R&D but stalls in procurement delivers no impact at scale.

By contrast, system-level approaches - where harvest, processing, supply assurance, and compliance are considered together - reduce friction before it appears.

This is why integration upstream matters. When ingredients are designed from the outset to align with how food is actually grown, processed, audited, and sold, reformulation becomes a commercial decision, not a speculative one.

Reformulation without consumer trade-offs

Crucially, low-friction reformulation also reduces consumer risk.

Many sustainability-led innovations ask consumers to change behaviour: accept unfamiliar ingredients, tolerate different textures, or pay a premium for virtue.

Low-friction approaches avoid that trap.

When reformulation focuses on familiar crops, familiar formats, and behind-the-scenes improvements - such as better utilisation of existing agricultural outputs - the consumer experience remains stable, even as the system improves.

That alignment matters. The fastest-scaling changes in food are rarely the most visible ones.

The strategic upside for food producers

For producers, the benefits of low-friction reformulation compound:

Faster internal alignment between technical, procurement, and commercial teams

Shorter approval cycles with retailers and brand partners

Lower execution risk at scale

Credible Scope 3 reductions tied to operational change, not offsets

Optionality to reformulate further without rebuilding infrastructure

In an environment where resilience is as important as differentiation, these advantages matter.

Closing thought: progress that fits the system

The food system does not need more disruption for its own sake. It needs progress that fits.

Low-friction reformulation recognises a simple truth: the fastest way to change the food system is not to fight its constraints, but to design within them — and quietly remove them over time.

For food producers under pressure to deliver cost control, sustainability, and reliability simultaneously, that approach is not conservative.

It is pragmatic.

It is scalable.

And increasingly, it is the only way change actually happens.

Read more here.

Yuka: The reformulation pressure food producers didn’t vote for (and why UPP is built for it)

Food companies are used to scrutiny. But the source of scrutiny is changing.

For most of the modern food system, legitimacy came from compliance: ingredient declarations, nutrition panels, and the fact a product met regulatory requirements. That framework still matters. But it no longer determines trust.

A growing share of consumers are outsourcing judgement to apps that sit outside the regulatory system entirely. One of the most influential is the French app Yuka.

It’s often described as a “food scanning” app. In practice, it functions more like a parallel credentialing system — one that is increasingly shaping what gets bought, what gets stocked, and what gets reformulated.

And that matters directly to the kind of upstream ingredient work UPP exists to enable.

A small app with outsized reach

Yuka launched in France in 2017. It now has more than 80 million users across 12 countries and 5 languages. In its home market, it’s used by roughly 1 in 3 adults (22 million users). In the US — where it launched in 2022 — it has reached 22–25 million users, and is now its largest and fastest-growing market, adding around 600,000 sign-ups per month.

It has processed more than 8.3 billion product scans to date (including 2.7 billion scans in 2024 alone), and built a database of 5 million product ratings across food and personal care.

The more important point is not the exact numbers. It’s what the numbers represent: Yuka has become a default layer of interpretation between the shelf and the shopper — without relying on traditional marketing or advertising. Growth is largely word-of-mouth.

That’s a sign of structural adoption, not a niche trend.

How Yuka scores food (and why it creates pressure)

Yuka assigns products a score from 0–100. The methodology is transparent in structure but opinionated in weighting:

60% nutritional quality, based on Nutri-Score

30% additives, with “high-risk” additives hard-capping a product at 49/100

10% organic dimension

Users don’t just see a score. They see a simple judgement (“excellent”, “good”, “mediocre”, “poor”) plus suggested alternatives.

This is where the commercial impact compounds. Yuka doesn’t just inform consumers. It redirects demand.

A product can be fully compliant and still become commercially fragile if it is scored poorly by a system consumers increasingly trust more than packaging claims or regulatory thresholds.

The part most manufacturers underestimate: the feedback loop

Yuka’s most consequential feature isn’t the rating.

It’s the mechanism that turns consumer dissatisfaction into direct reformulation pressure.

From inside the app, users can message brands with one click, sharing low product scores and urging reformulation. That turns millions of consumers into a distributed, always-on feedback loop.

Historically, reformulation pressure came from a small number of places:

regulators

retail buyers

internal nutrition targets

NGOs and media cycles

Yuka adds something different: persistent, product-specific scrutiny at the point of purchase, applied at scale, and repeated every day.

For producers, that changes the cost of inaction. It also changes the timeline. This isn’t a once-a-year strategy discussion. It’s a live operational risk.

Why this matters: reformulation is no longer just innovation. It’s defence.

Reformulation is often framed as innovation: new ingredients, new claims, new launches.

In reality, reformulation tends to fail for a more basic reason: it introduces too much friction into systems that are already under pressure.

Food manufacturers are balancing cost volatility, labour constraints, retailer scrutiny, Scope 3 accountability, and increasingly conservative capital environments — while maintaining taste, texture, safety, and margin.

High-friction reformulation introduces compounding risks: changes to processing lines, new allergen or regulatory complexity, uncertain supply at scale, sensory uncertainty, and additional approval cycles with retailers.

This is why many reformulation programmes quietly revert to incremental tweaks, even when bigger changes would be strategically smarter.

Yuka accelerates that reality. It makes the downside of “good enough” more visible.

Why this connects directly to UPP

At UPP, we’ve always assumed the food system won’t change through consumer behaviour alone.

Public health already tells us that behaviour change is unreliable — even when the stakes are personal health. So it’s unrealistic to expect consumers to overhaul their diets to reduce carbon emissions, improve nutrition, or avoid ultra-processing.

That doesn’t make consumers the problem.

It makes system design the problem.

Yuka doesn’t contradict that view. It reinforces it — from the opposite direction.

Consumers aren’t being asked to become perfect. They’re being given a tool that makes certain products feel harder to trust, and nudges them toward “cleaner” formulation logic. Whether or not you agree with Yuka’s weighting, the direction of travel is clear:

shorter ingredient lists

fewer additives that sound synthetic or unnecessary

more nutrition per bite

more explainable inputs

The industry can treat this as a communications challenge, but it’s more accurately a formulation and systems challenge.

And this is where UPP’s model becomes relevant.

UPP works upstream, taking under-utilised vegetables and converting them into food-grade protein and fibre ingredients that integrate into mainstream manufacturing. The goal isn’t to create novelty. It’s to remove friction.

Because the fastest way to improve food isn’t to ask consumers to change what they buy. It’s to improve what goes into the products they already buy — quietly, at scale, without disrupting production reality.

Low-friction reformulation isn’t a “nice to have” anymore. It’s becoming a strategic requirement.

What “Yuka-proofing” actually looks like

For most producers, the practical response to Yuka isn’t to optimise for a perfect score. It’s to reduce the surface area of vulnerability:

simplify ingredient systems where possible

replace fragmented additive stacks with more integrated, crop-derived functionality

increase protein and fibre density without making products heavier or harder to tolerate

improve label familiarity without sacrificing performance

In other words: reformulate in ways that don’t break the system.

This is exactly why familiarity and integration matter. Ingredients that behave predictably in standard manufacturing processes, arrive with procurement-grade documentation, and can replace multiple functions at once are more adoptable than technically impressive solutions that introduce operational risk.

Closing thought: a parallel credentialing system is now in play

Yuka has created a parallel credentialing system that influences consumer choice regardless of what regulators permit.

For food producers, the question isn’t whether Yuka’s scoring is fair.

It’s whether your products can withstand scrutiny from systems you don’t control.

In that environment, the winning strategy isn’t loud disruption. It’s quiet upstream improvement: better nutrition density, fewer unnecessary additives, simpler ingredient logic, and reformulation that fits existing manufacturing constraints.

That is what UPP is built to enable.

Quiet change. Upstream. At scale.

Clean ingredients that sound natural - and why that suddenly matters again

For years, the food industry has treated “clean label” as a marketing problem.

Remove an E-number.

Use "store cupboard ingredients"

Reduce the length of ingredient declarations on back of pack.

What’s changed recently is not the existence of processed food - it’s the level of public scrutiny around how food is processed, why, and whether the trade-offs are still justified. The debate has re-entered the mainstream.

From Joe Wicks: Food for Fitness to the success of Chris van Tulleken’s “Ultra-Processed People”, consumers are being exposed - often for the first time - to the idea that not all processing is equal, and that formulation decisions made far upstream can shape health, trust, and perception downstream.

For food producers, this creates a familiar tension.

The system still needs processed food.

Scale still requires consistency, safety, and shelf life.

Cost pressure has not gone away.

But the tolerance for ingredients that sound synthetic, opaque, or unnecessary is narrowing. And that matters — not because of ideology, but because perception now influences risk.

The quiet return of ingredient scrutiny

What’s striking about the current moment is how little it resembles previous “clean eating” cycles. This is not about superfoods or exclusion diets.

It is about processing logic.

Both the documentary and the book focus less on individual nutrients, and more on the architecture of modern food: fractionation, recombination, texture engineering, and the substitution of whole-food function with isolated additives.

That framing resonates because it aligns with something food manufacturers already know internally: Many formulation decisions were made to solve industrial constraints - not nutritional ones.

Those decisions made sense at the time. But some of their side-effects are now visible to consumers in a way they weren’t before.

Why “natural-sounding” ingredients are not about optics

There’s a temptation to treat this moment as a communications challenge.

Change the language.

Control the narrative.

Re-educate the consumer.

That approach misses the point.

What consumers are responding to is not branding — it’s credibility. Ingredients that sound natural tend to share three characteristics:

They originate from recognisable crops or processes

They perform multiple functions, rather than replacing each one with a separate additive

They can be explained without a chemistry lesson

This is not nostalgia. It’s cognitive load. When ingredient lists become shorter and more intuitive, trust increases - even if the product remains processed.

Processing is not the enemy - fragmentation is

One of the most unhelpful conclusions drawn from the “ultra-processed” debate is that processing itself is the problem. It isn’t.

Processing is what allows food to be safe, affordable, and widely available.

The issue is how fragmented processing has become.

Over time, many foods have been deconstructed into ever more specialised inputs -stabilisers, emulsifiers, texturisers, isolates - each solving a narrow technical problem, often sourced from different global supply chains. The result is food that works industrially, but looks and feels increasingly abstract to the people eating it.

Reversing that trend does not require abandoning processing. It requires re-integrating function.

When one ingredient can do the work of many

From a formulation perspective, the most powerful ingredients today are not the most novel. They are the ones that:

deliver protein, fibre, and functionality together

replace multiple additives with a single crop-derived input

integrate into existing processes without re-engineering lines

arrive with procurement-grade traceability and allergen clarity

This is where “clean” stops being about purity and starts being about efficiency - fewer ingredients, fewer suppliers, fewer explanations.

For manufacturers under pressure to reduce cost, risk, and Scope 3 emissions simultaneously, this matters more than philosophy.

Clean labels as a by-product of better system design

The most scalable changes in food rarely happen because consumers demand them explicitly. They happen because producers redesign systems in ways that quietly remove friction.

When ingredients are:

derived from familiar crops

processed through transparent, auditable systems

supplied regionally rather than globally

used to replace several additives at once the label improves as a side-effect.

Not because anyone set out to chase a claim — but because the system became simpler.

That distinction is important.

Why this matters now - commercially, not culturally

The current focus on ultra-processing will not last forever. But its effects on risk perception, retailer scrutiny, and regulatory attention already matter. For food producers, the question is not whether to respond – it is how.

High-friction reformulation in response to public pressure often creates more problems than it solves.

Low-friction reformulation - using ingredients that behave like food, sound like food, and come from food - creates optionality.

It allows producers to:

simplify labels without compromising performance

reduce additive dependency without redesigning factories

respond to current media pressure without chasing trends

future-proof portfolios against shifting definitions of “acceptable” processing

That is not a consumer strategy. It is a resilience strategy.

Closing thought: familiarity scales faster than novelty

The food system does not need to swing from hyper-processed to idealised whole foods. It needs better integration between agriculture, processing, and formulation - so that ingredients once again look and feel like they belong in food.

In a world where scrutiny is rising but tolerance for disruption is low, the safest path forward is not to fight processing - but to make it quieter, simpler, and easier to explain.

Clean ingredients that sound natural are not about going backwards. They are about rebuilding trust - one formulation decision at a time.

Read more here.

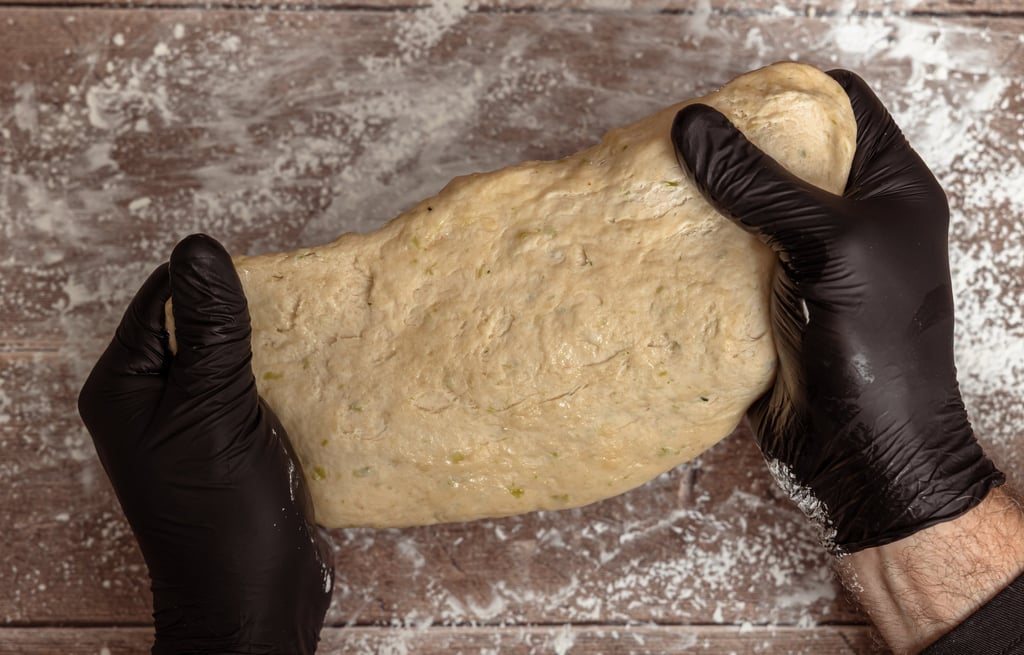

The most advanced taste tool we have is still a Chef

Some universities are trying to build an artificial tongue - a sensor system that can “measure” mouthfeel. And to be fair, the ambition makes sense. Mouthfeel is hard to quantify, and harder still to replicate at scale.

But at UPP, we back the Mark 1 human, or “Joe”.

Because food isn’t for sensors. It’s for people.

And if you want to innovate in food - really innovate, in a way that survives the journey from idea to supermarket shelf - you need to keep people at the heart of the process. That starts with the person who understands the eating experience better than anyone else: the chef.

The chef is the hero - not the lab

There’s a myth that food innovation is mainly about technology: new processing, new ingredients, new data, new optimisation.

In reality, the breakthrough usually comes from a much simpler place:

A chef tasting something and saying, “Not yet.”

That moment matters because it’s where the real standard is set. Not “does it meet the spec?” but:

Does it feel right when you chew it?

Does it eat like food?

Would you actually want a second bite?

A supermarket product doesn’t win because it’s clever. It wins because it’s comfortably familiar - and quietly better.

That’s the chef’s territory.

The creation journey: from idea to shelf

When we build a new meal concept for retail, it starts the same way most great food does: with a simple question.

What are we trying to make people feel when they eat this?

Not nutritionally. Emotionally. Practically. In the real world.

Because the moment it lands in someone’s basket, the rules change. It’s no longer a prototype. It’s dinner on a Tuesday. It has to work when someone is tired, hungry, price-sensitive, and not interested in being educated.

So the chef begins building - testing flavour, texture, aroma, and structure. The goal isn’t novelty. It’s confidence.

And this is where “mouthfeel” stops being a buzzword and becomes a make-or-break reality.

Mouthfeel is where good intentions go to die

You can have the best nutrition profile in the world and still fail on shelf if the eating experience is wrong.

Too dry.

Too grainy.

Too bouncy.

Too “engineered.”

Consumers don’t describe it that way, of course. They just say:

“I didn’t like it.”

Or worse - they don’t say anything at all, and they simply don’t buy it again.

That’s why mouthfeel is one of the highest-leverage parts of product development. It’s also why we don’t believe the solution is to remove humans from the loop.

We don’t want food assessed by something that simulates a tongue.

We want it assessed by the people who actually eat it.

Technology matters - but it plays a supporting role

UPP is technology-enabled, and we’re proud of that. We work upstream, turning under-utilised vegetables into functional ingredients that help food manufacturers improve nutrition, efficiency, and resilience.

But we’re clear-eyed about something: Technology doesn’t make food good. People do.

Our ingredients are designed to integrate into real manufacturing and real products - but they still have to pass the same test every time:

Does it taste good? Does it feel right? Does it work as food?

That’s why chefs are not an optional extra in innovation. They are the decision-makers who protect the eating experience as products scale.

Keeping people at the heart of innovation

The food industry is under pressure from every angle: cost, labour, emissions, reformulation, protein targets, fibre gaps, clean label scrutiny.

In that environment, it’s tempting to treat product development like a maths problem.

But food isn’t just a system of inputs. It’s a human experience.

And the fastest way to build the wrong future is to optimise everything except the thing that matters most: whether people actually enjoy eating it.

That’s why we keep coming back to the same principle:

Food is for people. So people belong at the centre of innovation.

Not as an afterthought. Not as a “consumer test” at the end.

Right at the beginning - with a chef, a spoon, and an uncompromising standard for what belongs on a plate.

Closing thought: trust the classical approach

We’re not against artificial tongues - they may well become useful tools for R&D.

But the best instrument we have for building food that works in the real world is still the simplest: A chef tasting, refining, and insisting that it eats like something you’d actually want to buy again.

The Mark 1 human remains undefeated.

We are not about restricting progress – we are leading the charge on utilisation and hybridisation – it’s about blending emerging technologies with classic approaches. Like everything else in food, it’s all about getting the blend right. And in a world obsessed with engineering the future of food, we think that’s worth remembering.

If people won’t change their diet to save their lives, why would they change it to save the planet?

For years, much of the food sustainability debate has rested on an uncomfortable assumption: that consumers will change first.

Eat differently.

Buy differently.

Pay more.

Care more.

Sometimes they do. Often, they don’t. And that’s not because people are ignorant or indifferent - it’s because food choices are made inside real constraints.

When there is too much month left at the end of the pay cheque, sustainability becomes a luxury. When time, money, and familiarity matter, people default to what works. That reality doesn’t make consumers the problem. It makes the system the problem.

At UPP, we don’t judge consumer behaviour - because judging behaviour doesn’t change outcomes. Designing systems that work within reality does.

Behaviour change is a weak lever - system change is a power enabler.

Public health has already taught us this lesson: If people won’t reliably change their diets to improve their own health, it is unrealistic to expect them to overhaul their food choices to reduce carbon emissions - especially when the alternatives are unfamiliar, more expensive, or harder to trust.

The food system cannot decarbonise by asking millions of households to behave differently every day. It can decarbonise by changing what goes into food: quietly, upstream, and at scale.

That is where leverage actually sits.

Waste is not a moral failure - it’s a design failure

Across UK and European agriculture, vast volumes of nutritious vegetables are grown every year and never enter the food system.

Not because they are unsafe.

Not because they lack nutritional value.

But because harvesting them is labour-intensive, uneconomic, or poorly integrated with downstream demand.

Those crops are left in fields or diverted to low-value uses, while food manufacturers import ingredients from halfway around the world to perform the same functions.

That isn’t a consumer choice problem.

It’s a systems design problem.

UPP exists to fix that. Using what already exists - before growing more. Our approach starts with a simple question: “What if we used the food we already grow — but don’t currently use - to replace ingredients that travel thousands of miles?

UPP works with wasted and under-utilised vegetables: grown in the UK where possible, and in Spain during winter when domestic supply isn’t viable

We don’t compete with fresh markets.

We don’t displace food from plates.

We work with plants that would otherwise be left to rot.

From those crops, we produce protein and fibre ingredients that:

displace globally sourced inputs

deliver lower CO₂ even if grown for purpose

and do so at a cost that works for real food systems

This is not about niche substitution. It’s about mainstream replacement. Sustainability that pays for itself scales faster. One of the reasons sustainability efforts stall is simple: they cost money. UPP’s model flips that logic. Because our ingredients are derived from side-streams and under-utilised crops:

farmers gain a new income stream from material that previously had little or no value

producers gain lower-cost ingredients that integrate into existing processes

retailers gain credible Scope 3 reductions tied to operational change

consumers get nutritious food at lower or equivalent prices

Margins improve instead of eroding. That matters - because the changes that last are the ones that make commercial sense. Technology is the enabler - not the point.

Yes, this is technology-enabled.

Yes, it’s patent-protected.

Yes, it involves automation, processing innovation, and system integration.

But technology is not the goal. We are not developing technology for its own sake. We are developing technology to achieve an outcome. Every decision is anchored to a single question:

Does this make the system work better - economically and environmentally — without asking people to behave differently?

If the answer is no, it doesn’t scale.

Quiet change beats loud disruption

UPP’s ingredients don’t ask consumers to learn new words, adopt new diets, or pay a premium for virtue. They sit behind the scenes - improving food by changing how it is made, not how it is marketed. That is why this approach works:

familiar crops

familiar foods

familiar buying behaviour

But with lower waste, lower emissions, and better economics embedded upstream.

Better for everyone — by design

This is systems-thinking applied to food:

Better for planters (farmers): new revenue, less waste, more resilient economics

Better for producers: lower costs, lower risk, low-friction reformulation

Better for people: nutritious, affordable food without behavioural trade-offs

Better for the planet: emissions reduced at source, not offset after the fact

But

No judgement.

No guilt.

No unrealistic assumptions about how people “should” behave.

Just a better system — designed to work in the real world.

Because the fastest way to change what people buy is not to ask them to change at all - it’s to change the system behind the shelf.

Read more here.

A World Without Cows: What happens when we optimise the wrong variable?

The film World Without Cows (https://worldwithoutcows.com/?) asks a deceptively simple question: “what would the world look like if cows disappeared?” It’s based on a white paper that appeared in Nutrition (https://www.livestockresearch.ca/uploads/cross_sectors/files/A-World-Without-Cows-Imagine-Waking-Up-One-Day-to-7.pdf) – the story is worth reading (https://worldwithoutcows.com/cows-disappeared-scientific-paper-film/)

It’s an emotionally charged premise because cows sit at the intersection of so many modern tensions - climate, land use, food security, rural livelihoods, nutrition, culture, and identity. But what makes the film valuable is not that it defends cattle uncritically, or dismisses the environmental case against them. It highlights something more important: the risk of treating complex food systems as if they have single-variable solutions.

In a moment where “remove the cow” is sometimes presented as a shortcut to sustainability, World Without Cows pushes back with an uncomfortable reminder: systems don’t behave like spreadsheets.

And food systems rarely reward simplification.

The temptation of the clean narrative

Food sustainability debates often gravitate toward clean, binary stories:

cows are bad

plants are good

methane is the problem

replacement is the answer

That narrative is emotionally satisfying because it offers clarity. But it can also become a trap. Because the real question is not whether cows have impact. They do. The question is what happens after we remove them - and whether the “solution” creates second-order consequences that are worse than the original problem.

This is where the film’s premise becomes useful: it forces us to consider the system response, not just the headline metric.

Behaviour change is a weak lever. System design is the power lever.

One of the biggest mistakes in sustainability strategy is assuming consumers will change first.

Eat differently.

Pay more.

Accept unfamiliar textures and ingredients.

Rebuild habits.

But public health already tells us how this goes: if people won’t reliably change their diet to improve their own health, it’s unrealistic to expect them to change it to reduce emissions - especially under cost pressure.

So if the goal is real-world impact at scale, the solution can’t depend on everyone making perfect choices every day.

It has to come from upstream changes that make the default food system work better - without requiring the public to become different people.

That is why we focus on system change, not food ideology.

Replacement strategies often fail because they introduce friction

The film indirectly exposes another commercial reality: even when the sustainability case for “cow-free” food is strong, replacement is hard to execute at scale. Because replacement strategies often come with high friction:

new supply chains

new processing requirements

new sensory compromises

new approval cycles

higher costs

unfamiliar ingredients and consumer scepticism

In practice, reformulation doesn’t fail due to lack of ambition. It fails because it introduces too much disruption into systems already under pressure.

That’s why “low-friction reformulation” matters: ingredients and approaches that reduce emissions, cost, and risk without breaking manufacturing reality.

A world without cows still needs protein, function, and affordability

Remove cows, and you don’t just remove emissions.

You remove a huge amount of:

high-quality protein

functional fat systems

nutrient density

agricultural value creation

rural economic stability

The question then becomes: what fills the gap?

Not in theory - in supermarkets, school meals, hospitals, and mainstream ready meals. At price points that normal households can afford.

And this is where many “cow-free” narratives become fragile: they assume the alternative system is already built, already scalable, already affordable, and already trusted.

It isn’t.

The better question: how do we reduce impact without breaking food?

This is why the most scalable sustainability strategies in food are rarely ideological. They are operational.

They focus on efficiency - using what we already grow more effectively - so that sustainability becomes a by-product of better system design.

At UPP, our work is built around that principle: using under-utilised vegetables and side streams and converting them into functional protein and fibre ingredients that integrate into mainstream manufacturing.

Not because consumers want to “eat side streams”.

But because the system is wasting nutrition at scale - and importing ingredients to replace functions that already exist in-field.

Waste is not a moral failure. It’s a design failure.

Hybridisation beats disruption: the fastest route to real impact

One of the most practical outcomes of the “world without cows” thought experiment is this: you don’t need total elimination to create meaningful change.

You need partial displacement at high volume.

That’s why we believe in ingredient stacking and hybridisation - not as a consumer trend, but as a systems strategy.

For example:

reducing meat inclusion in processed foods while maintaining taste and affordability

increasing nutrition density by adding vegetable-derived protein and fibre

improving texture and yield without additive-heavy formulation

This is not “anti-meat”. It’s pro-efficiency.

It reduces emissions faster because it fits inside existing buying behaviour and existing manufacturing.

Quiet change beats loud disruption.

The film’s real message: beware single-variable optimisation

World Without Cows is ultimately a warning against solving food sustainability by removing one component and assuming the rest of the system will self-correct. The interview with the film makers is worth watching: https://worldwithoutcows.com/the-making-of-world-without-cows

Because the food system is not a single problem.

It’s a network of constraints: nutrition, economics, labour, land, resilience, consumer trust, processing infrastructure, and supply chain risk.

If we optimise only for “remove cows”, we may unintentionally worsen:

nutrition density

affordability

land-use outcomes

reliance on imported, fragmented ingredients

food security and resilience

And we may still fail to deliver the climate gains we expect - because the replacement system carries its own footprint, frictions, and unintended consequences.

Closing thought: don’t aim for a world without cows - aim for a world that works

The most useful takeaway from World Without Cows isn’t that cattle are perfect, or that nothing should change.

It’s that the path to better food systems isn’t purity.

It’s practicality.

The food system will not decarbonise through moral pressure or consumer behaviour change. It will decarbonise when upstream design makes lower-impact food the easiest, cheapest, most reliable option — for producers, retailers, and households.

That is the work:

not removing cows to feel certain,

but redesigning systems to reduce waste, improve nutrition, cut Scope 3 emissions, and keep food affordable - at scale.

Progress that fits the system is the only kind that lasts.

Upcycling as Infrastructure: Why UPP Joined the Upcycled Food Association

For much of UPP’s development, we’ve worked quietly upstream — focused on harvest automation, processing infrastructure, and ingredient integration rather than labels, claims, or categories.

That hasn’t been accidental.

Our view has always been that the fastest way to improve nutrition and reduce environmental cost is not to ask consumers to change what they buy, but to change what goes into food - reliably, at scale, and without adding friction to systems that are already under pressure.

In that context, UPP’s decision to join the Upcycled Food Association is less about affiliation, and more about alignment.

Why “upcycled” fits UPP’s model - without changing it

The term upcycled food is often associated with consumer-facing products and on-pack certification. That’s not where UPP operates.

Our work sits earlier in the system: taking under-utilised crops and side-streams that already exist, and converting them into food-grade protein and fibre ingredients that integrate into mainstream manufacturing.

But at a system level, the logic is the same.

Upcycling is not about novelty. It’s about using what we already grow more effectively - before we grow more, import more, or extract more.

That principle has guided UPP from the start:

working with vegetables that are left in-field or diverted to low-value pathways

converting them into ingredients that displace globally sourced inputs

improving nutrition density while lowering embedded emissions

doing so at costs that work for real food producers

The Upcycled Food Association (https://www.upcycledfood.org/) exists to accelerate exactly that kind of system-level change - not by reinventing the food system, but by reconnecting its broken loops.

From fragmented effort to shared infrastructure

One of the persistent challenges in food sustainability is fragmentation:

Farmers optimise yields.

Manufacturers optimise processes.

Retailers optimise risk.

Consumers optimise price and familiarity.

Waste, emissions, and nutritional dilution tend to sit in the gaps between those objectives.

The Upcycled Food Association plays an important role by creating shared standards, language, and credibility around a simple idea: that waste is not a moral failure, but a design failure - and one that can be fixed.

For UPP, joining the Association is a way of contributing operational proof to that mission.

Not theory.

Not aspiration.

But infrastructure that works under commercial conditions.

Expanding the platform - including into California

While UPP’s current operations are anchored in the UK and Europe, our ambition has always been to build a replicable harvest-to-ingredient platform, not a single geography–bound solution.

California is a natural next step. It is one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions — and also one of the most constrained:

labour availability is structural, not cyclical

water and input efficiency are under scrutiny

food waste volumes are significant

nutrition and sustainability pressures intersect directly

These are exactly the conditions UPP’s system is designed for.

By engaging with the Upcycled Food Association’s network in the US, UPP aims to:

collaborate with growers and processors facing similar structural challenges

adapt our approach to crops and conditions specific to California

contribute to a broader ecosystem focused on nutrition, waste reduction, and commercial viability

ensure that expansion is grounded in existing supply chains, not built in isolation

This is not about exporting a finished solution. It’s about deploying a proven logic into a new context - carefully, collaboratively, and with local relevance

Improving nutrition without asking people to try harder

A consistent thread in UPP’s work - and one shared by the Upcycled Food Association - is realism about behaviour. If people won’t reliably change their diets to improve their own health, it is unrealistic to expect them to overhaul their food choices to save the planet.

That doesn’t make consumers the problem.

It makes system design the problem.

Upcycled ingredients, when done properly, allow nutrition to improve quietly:

more protein and fibre per bite

fewer imported, fractionated inputs

familiar foods made better upstream

No new habits.

No premium positioning.

No behavioural trade-offs.

That is how change actually scales.

Reducing environmental cost where it matters most

From an environmental perspective, the most meaningful reductions rarely come from offsets or end-of-chain claims. They come from using existing land, crops, and inputs more efficiently.

By turning under-utilised vegetables into ingredients that replace conventional alternatives, UPP’s model:

reduces waste at source

lowers the need for additional agricultural production

cuts transport and processing emissions embedded in global supply chains

creates verifiable Scope 3 reductions tied to operational change

The Upcycled Food Association provides a framework for recognising and accelerating these kinds of outcomes — grounded in evidence rather than marketing.

A shared direction, not a new identity

Joining the Upcycled Food Association does not change UPP’s role.

We remain an upstream, B2B ingredient platform.

We remain focused on low-friction reformulation.

We remain committed to designing within real-world constraints.

What it does signal is intent:

to participate in a broader, international effort to redesign food systems around efficiency rather than excess

to contribute practical infrastructure, not just ideas

to expand responsibly - including into California - in partnership with those already doing the work

Progress in food rarely comes from loud disruption. It comes from quiet alignment, repeated at scale.

That’s what upcycling looks like when it’s treated as infrastructure - and why this is a natural next step for UPP.

Ingredient stacking: the fastest route to lower-carbon food that still tastes like food

Most of the food industry’s sustainability debate still gets stuck in the same place: replacement.

Replace meat with plants.

Replace dairy with alternatives.

Replace “bad” ingredients with “better” ones.

The problem is that replacement strategies often come with high friction: new supply chains, new processing behaviour, new allergen complexity, new sensory problems, and – critically - new consumer compromise.

That’s why so many “climate-friendly” products struggle to scale. Not because the science is wrong, but because the system is real.

A more practical approach is emerging—one that fits the way food is actually made, bought, and eaten: ingredient stacking.

Not a new category. Not a new diet.